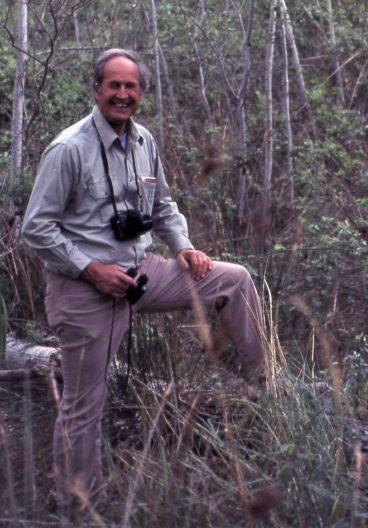

SEFS remembers College of Forestry Professor Emeritus Reinhard F. Stettler

We are saddened to share the news that Professor Emeritus Reinhard (Reini) Stettler passed on December 9, 2024. He was 94. Professor Emeritus Stettler was hired in 1963 as an Assistant Professor in the University of Washington’s College of Forestry, now the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. He is remembered by his many students, colleagues and friends for his insatiable curiosity, generous collaborative spirit and infectious enthusiasm. His son, Daniel Stettler, shared Professor Stettler’s obituary – you can learn more about his time here at the University of Washington and his incredible work as a plant geneticist below.

A memorial service for Reini Stettler will be held on Saturday, April 5 2025 at the Visitor Center of the Washington Park Arboretum. The indoor and outdoor spaces have been reserved from 11AM-3PM.

Reinhard (Reini) Stettler (December 27, 1929 – December 9, 2024)

Professor Emeritus Reinhard (Reini) F. Stettler died on December 9, 2024 at the age of 94. Born in Steckborn, Switzerland, he received his undergraduate degree in Forest Engineering from the ETH in Zürich (1955), then crossed the Atlantic to pursue graduate coursework at the University of British Columbia (1955-56). Reini worked as a Research Officer for the British Columbia Forest Service (1956-58) and as a Research Associate at the Swiss Forest Research Institute (1958-59) before returning to academia.

Reini earned his Ph.D. in Genetics at the University of California, Berkeley in 1963. Always a free thinker and iconoclast, rather than carry out his doctoral research on a commercially-important forest tree species, as was (and is) the tradition in his chosen field of forest genetics, he instead undertook a project to elucidate the role of variants in a single gene (LANCEOLATE) in determining differences in the architecture of leaf shape in the much more genetically-tractable domesticated tomato.

Reini’s penchant for blazing his own trail continued when he was hired in 1963 as an Assistant Professor in the University of Washington’s College of Forestry (later, Forest Resources, now the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences). Although it was made clear to Reini that he was expected to establish a Douglas-fir breeding program to support the state’s timber industry, he had other plans – he intended to identify and develop an entirely new model system for fundamental research in woody plant genetics, without regard to its commercial importance. Reini’s deep knowledge of the natural history and reproductive biology of forest trees led him to choose the genus Populus (poplars, cottonwoods, and aspens) for his studies because of its genetic tractability: a short interval between generations, ease of vegetative reproduction (cloning), rapid growth, and potential for artificial hybridization between species.

His early research was focused on developing state-of-the-art genetic tools for Populus, including genetically pure (homozygous) lines by haploid parthenogenesis and a “mentor pollen” technique for making both parthenotes and (unexpectedly) hybrids between distantly-related Populus species (Nature 1968 219:746–747). Among the many experimental interspecific crosses that he created, Reini observed that “TD” hybrids between the Pacific Northwest native black cottonwood (P. trichocarpa) and eastern cottonwood (P. deltoides) grew exceptionally rapidly – as much as 3m in height per year.

In 1971, Reini contacted soil scientist Paul Heilman at Washington State University’s Research and Extension Center in Puyallup to gauge Paul’s interest in testing the growth of TD hybrids against a large number of wild P. trichocarpa clones that Paul had collected, and so began a collaboration that would last more than 25 years and give birth to a new forest products industry in Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia. By the mid-1970s it was apparent that the TD hybrids were astonishingly productive. In 1978 the U.S. Department of Energy awarded a large grant to Reini and Paul to develop and test poplar hybrids as a source of woody biomass for renewable energy. This grant was funded continuously for the next 20 years and underwrote a collaborative network that grew to include physiologists, pathologists, chemists, molecular biologists, and ecologists around the world. Crown-Zellerbach (and its James River successors), Boise Cascade, MacMillan Bloedel, Weyerhauser, Scott Paper, International Paper, Potlatch, and other forest products companies joined and supported the research effort, and several of them made extensive commercial use of the highest-performing hybrid clones in large plantations, many of them visible along the I-5 corridor today.

Reini was as inspiring in the classroom as he was in the field. He believed that students needed to go into the natural world to develop scientific questions from their own observations, and to answer these questions by applying the scientific method. He met individually with every student, offering both support and challenge to their observations and conclusions. In 1990 Reini won the university-wide Distinguished Teaching Award for undergraduates. His graduate students and postdocs have gone on to prominent positions in academia, industry, and government agencies.

In addition, Reini extended his teaching beyond the university as the director of the Silviculture Institute for mid-career foresters who came from international agencies as well as from private industry. For a number of years, he taught courses as a field-studies teacher in Advanced Placement Biology for high school students at his favorite bend in the Snoqualmie River. All these activities eventually led Reini to write and illustrate a book in 2009 entitled “Cottonwood and the River of Time: On Trees, Evolution and Society”. He felt that after so many years of research and teaching it was important to write for a broader audience.

Reini described himself as a student of nature. Natural form—its unfolding in the individual, its evolution over time, its diversity in the aggregate—was a perpetual fascination for him. He felt fortunate to be able to convey this to those around him and in return enjoyed seeing how they put that to creative use. His letters tell us that he “lived in the grand arc of nature and saw the beauty in the continual flow of generations. The leaves that fall in autumn are both an end and a promise. Life in its many forms continues. What comfort to return your molecules to the earth for what is yet to come!”

Reini will be long remembered by his many students, colleagues, and friends for his insatiable curiosity, generous collaborative spirit, infectious enthusiasm, and high standards of scientific rigor and ethics. This is the legacy of a life well lived.

Reini is survived by his older brother Emanuel, his son Daniel, his grandson Nico, Daniel’s partner Penelope West, Nico’s wife Nicole Karsch, and Daniel’s former wife Andrea Kohler.

Lynda V. Mapes, environmental reporter for The Seattle Times penned a lovely piece on the life and work of Reinhard Stettler. Read the article.

Memorial contributions may be made to the University of Washington’s Friends of the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences Fund to support a Reinhard Stettler Annual Excellence in Biology Lecture. Checks may be sent to: University of Washington; Attn: Gift Services; Box: 359505; Seattle WA 98195-9505. Donors should include a note in the memo line: In memory of Reinhard Stettler. A celebration of life will take place in Seattle in the spring and another in early summer in Kandersteg, Switzerland.