What’s happening inside a crow’s brain when it thinks about using a tool? Researchers at the University of Washington used to peer inside the brains of crows as they were challenged with a difficult task that required stone tools to solve.

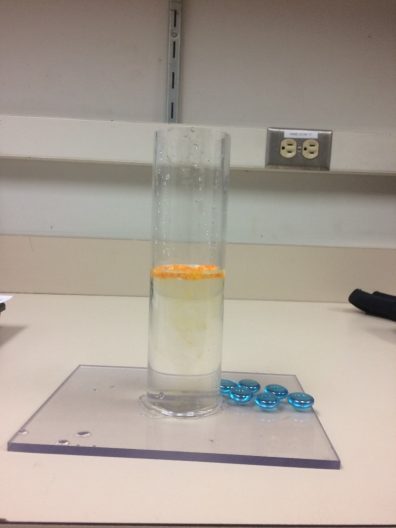

The researchers showed crows an Aesop’s fable paradigm; a clear tube partially filled with water containing a floating food item. The birds had to learn to to a level that enabled them to reach the food reward.

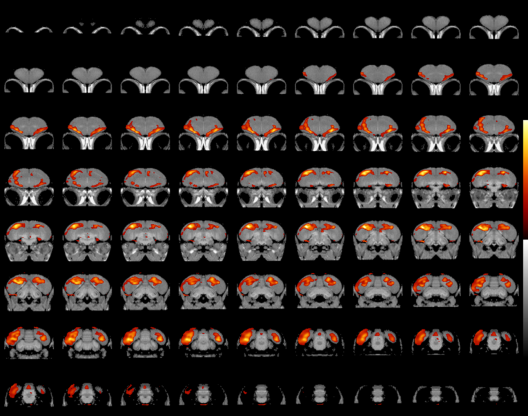

The researchers recorded relative brain activity when the crows were first exposed to the Aesop task, then spent several months training them to solve it before scanning their brain activity a second time. The proficiency in learning the task affected brain activity between the two scans.

“Talent matters,” said lead author Loma Pendergraft, an instructor affiliated with the UW Department of Psychology and the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. “We found that naïve crows – who had never seen the apparatus before – showed more activity in neural circuits that govern sensory and higher-order processing. They were taking in a lot of information and thinking hard about it. But, if they became proficient at using tools to solve the task, we saw a big shift away from those regions and into areas associated with motor learning and tactile control.

This suggests that crows are like humans; we both use the parts of our brain that allow us to think and consider the actions needed to learn a skill, but as we master that skill, we start relying on muscle memory instead. According to coauthor John Marzluff, professor emeritus of the UW’s School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, “It is like a master skier prepping for a slalom run. They work through each turn mentally as they await their start. The master crows did likewise, mentally working through the movements of their bodies, especially their beaks that would be needed to pick up and drop the stones.”

The team published their results Oct 20 in Nature Communications.

Training the crows was a significant challenge the team had to overcome. “American crows are not regular tool users,” said Pendergraft, “and I was at my wits’ end trying to get them to learn how.” He ultimately succeeded in training some of the crows by tying the stones to lines that were anchored inside the tube, then balancing the stones along the tube’s rim. When the hungry crow tried to grab the food floating just out of reach, they usually inadvertently knocked a stone into the tube’s interior, bringing the water level upward. “Once they understood that cause and effect relationship, it wasn’t long before they started picking stones off the ground to drop inside.”

Curiously, not all crows were equally adept at using tools; female crows were far more likely than the males to solve the task. “All of our adult females learned to use tools. Only one male figured it out,” said Pendergraft, “we see the same female bias for tool use in dolphins, chimps, and bonobos.” He speculates that this trend may be because female crows tend to be smaller than males and may rely more on clever strategies to navigate crow society, whereas the larger males can get their way through their size and strength. Ultimately, it is a question for future study.

Additional co-authors on this paper are Donna Cross, an associate professor at the University of Utah; Toru Shimizu, a professor and associate dean at the University of South Florida; and Chris Templeton, an assistant professor at Western Washington University.

This research was funded by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Higher Education and Training Program, the NSF GRFP, the Seattle ARCS Foundation, the James Ridgeway Professorship, the NIH (grant: 1S10OD017980-01), and the NERC (grant: NE/J018694/1).

This release is shared with permission from lead author Loma Pendergraft.